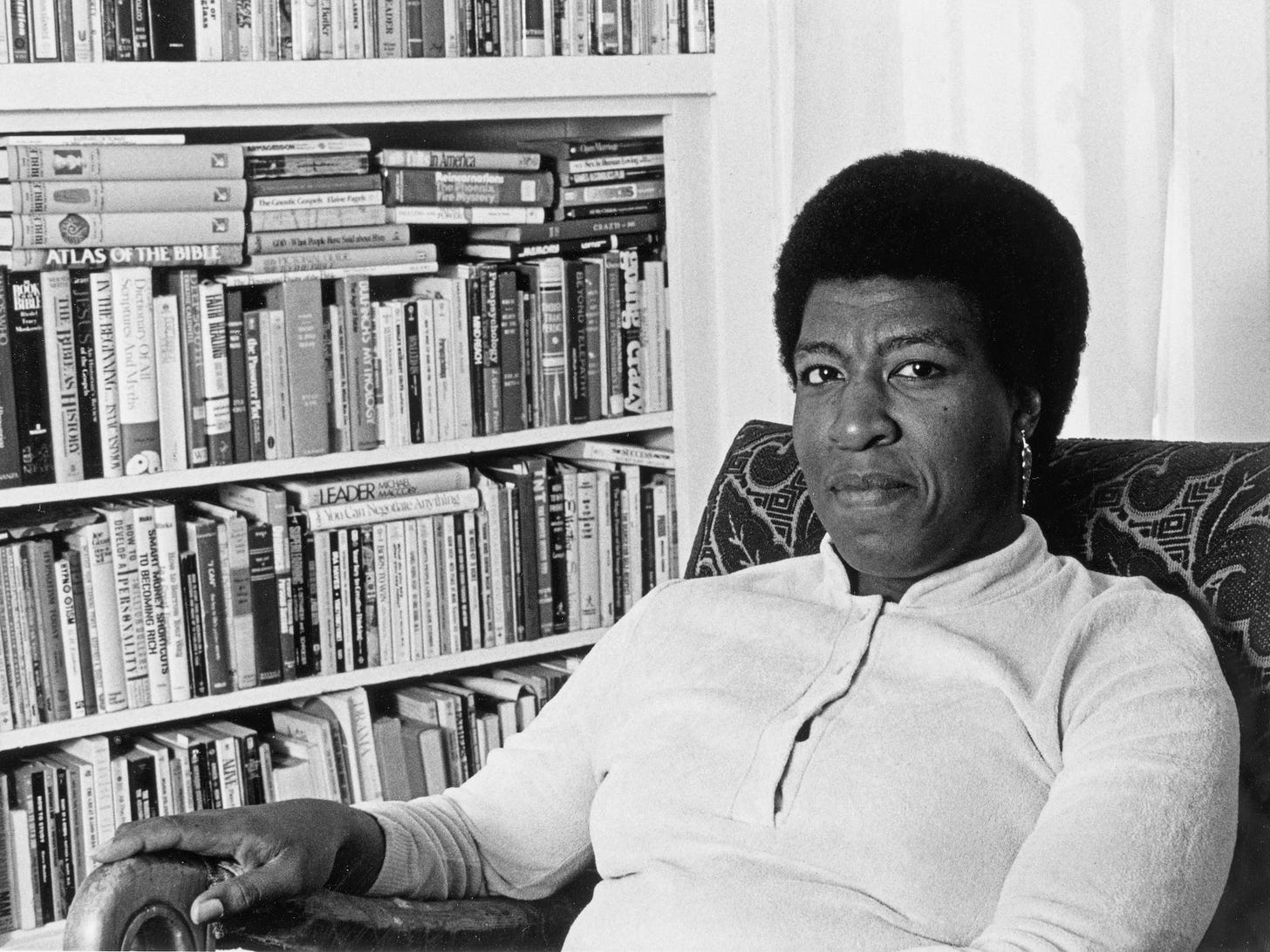

There Are Black People in the Future: Why I'm Reading Octavia E Butler This Year

Reading the mother of Afrofuturism might help us respond to the question: “Why does your fantasy exclude Black people?”

This title is inspired from Alisha B. Wormsley’s work. She’s described some of the associated work in Black Futures (ed. Kimberly Drew and Jenna Wortham). In that essay she maintains that she does not own the phrase, but I’d still like to credit her for it.

“Why aren’t there Black people in your fantasy?”

I saw this question in the midst of discourse about why so few fantasy movies, shows, novels, featured specifically Black people.

Like so many of the moments and questions that end up changing my own trajectory, I don’t remember who asked the question. I think I saw it on Twitter, but it could have been in an Instagram comment about The Rings of Power, a comment by a guest on MSNBC about Bridgerton, or in any number of panels at a book convention or author event. Wherever it came from, the question hasn’t left my mind.

So much conversation around diversity and inclusion can often feel like comparing groups of people against a color wheel and asking “Have we hit the quota?” This is a misunderstanding. For me, the question “Why aren’t there Black people in your fantasy?” is the test that all speculative fiction should be measured against.

When we fantasize, why do we exclude races of people? When we think about the future, how are we projecting experiences other than our own?

White people are on track to be a minority in the United States, and the rate of change will only be slowed by racist partnering decisions by white people, conscious and unconscious. No matter what variation of caramel-colored skin becomes dominate over the next centuries (if human beings survive), we will not be all white in the future. Neither will we be all Black, or Asian, or any other currently named racial group or nationality-named-as-race. Borders shift and change, as will our national identities and how they’re tied to race, but color will not evaporate.

There were Black people in Ancient Greece, contemporary to the events of Gladiator, many in privileged positions. There were powerful Black people in the court of Great Britain in the 1700s - Queen Charlotte very well may have been Black. Our current conceptions of race were invented in the 1600s, mostly as a way to maintain the Atlantic slave trade. As we understand it today, race is a capitalist invention. Our imaginations and historical records are impotent if we use only those pathetic metrics.

This is critical to understanding the past and future. And it’s not new.

Frank Herbert’s Dune understands and grapples with how race and identity play into the future, and it is so fundamental to the text that it cannot be a plot point, it’s part of the water his characters swim in. As a result, it’s often missed or misunderstood by contemporary readers who are primed to think about race acutely. The Fremen on Arrakis are a multi-racial people, colonizers themselves, having arrived on their ships not terribly long before the rest of the empire. They adopted behaviors of Earth’s Middle Eastern people to survive on their shiny new homeworld of Dune, but they are not “Middle Eastern” as there was no middle east millennia after our time. Their skin colors range from lily white to richest Black, as described in the text and faithfully portrayed in Villeneuve’s films. They were colonists from a colony ship that wore a costume until it was no longer a costume. They faked it til they made it.

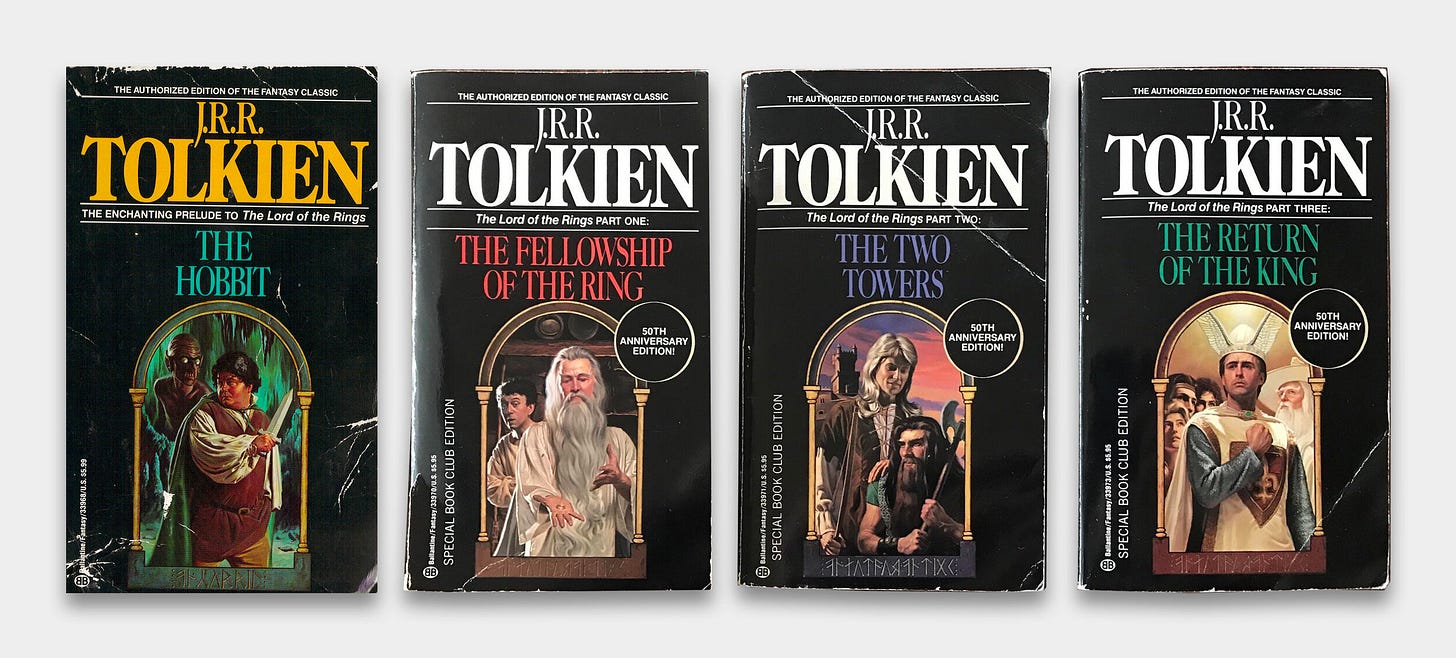

But this is not the case for most fantasy and science fiction authors, especially before the 1990s. Even The Lord of the Rings is rife with explicit and implicit racial and gender bias, worse than many of Tolkien’s contemporaries, despite its holistic and expressive exploration of the breadth of human grief and joy and hope and hopelessness.

Intentions can be debated all day, but a flat white future is a choice, a bleach white fantasy is a choice.

When it comes to understanding any social moment, I try to look at who has been correct and dig into their work. As Sarah Kendzior1 says

It is very bad in America to be right too early. It is considered a sin in journalism to tell the public what you have learned in real time, both because you are going against the tide of profit motive, but mostly because it destroys plausible deniability for the corrupt and powerful.

This is why prophets are hard to find. They go unpublished. They are derided. They’re buried. The Cassandra effect. It means seeking out work that hasn’t sold best or been celebrated by gatekeepers. But folks who are repeatedly correct are worth finding.

Octavia E. Butler is one of these people.

Butler found traditional success only after decades of publishing and only shortly before her death. Even published, she had to fight to be fairly compensated. But now, in the years she set Parable of the Sower, as we experience the world she described decades ago, we see how spot-on she was. She correctly predicted a future that people didn’t want to admit.

Octavia E Butler is widely considered the mother of Black sci-fi, if not the first to ever do it. It wouldn’t be my place to bestow any titles, but for me she represents a kind of sidestepping of the white supremacist narrative lineage. While she exists in the context of writers like Asimov and Lovecraft, she doesn’t inherently carry the water of their racial and racist instincts, and thus creates opportunities within her narratives that are full of other kinds of potential.

I will say, the infrequency that Butler mentions race, especially as a function of plot or animating themes, is strange. I want to call it “confusing” and “weird” and “beguiling,” but each of those words carry either negative or provocative implications that are inaccurate. Her relative silence on those specific themes create their own gravity, an almost anti-Chekov’s gun. We know it’s there and she almost never fires it.

My own expectation also comes from a place of centering my own whiteness. A Black writer writing about Black people set in “post-racial” futures need not include a discussion of race, a concept invented by capitalist, colonial white people. The culture that created the racism I expect was from a culture that the narrators of her Patternist Series consider lesser beings. In her Lilith’s Brood trilogy that culture is dead. Perhaps Butler was operating from a position beyond these considerations, which is inherently and progressively radical.

Race and racism are certainly evident in Kindred, which includes a lot of slavery narrative, and Fledgeling includes Blackness as a preferable trait. But considering her position as “The Mother of Afrofuturism”, there is little overt discourse around race.

While there is brilliant scholarship about slavery narratives and racial analysis in her work, Butler herself claims to have not included these intentionally. That doesn’t mean they don’t exist, but they’re not as explicit as many contemporary publications.

Reading Butler today, race becomes the untold story around which her stories revolve2. Her work is soaked in the benefits of proper birthing - The Patternist Series, Lilith’s Brood, and Fledgeling are all obsessed with eugenics, only the last accounting specifically for race. A Black writer obsessed with eugenics is inherently a commentary on race, especially in American culture, even if it’s unintentional. This is something topic I know nothing about. Butler completionism might illuminate some.

So, “Why aren’t there Black people in your fantasy?” Because the historically dominate voices approved by gatekeepers are of a system that erases Black people and other minorities. While this system has changed over the last four hundred years, it hasn’t died yet. Even as it proves its own brokenness it also continuously armors itself in a poor, fleshy patchwork of shielding. But writers like Butler encourage us not to ignore the reality, but instead offer the opportunity to see beyond it.

I don’t know if Octavia E Butler is instructive for us in our specific 2025 moment because she is not engaged in savior narratives or national revolutions that also incidentally save the world (thank God). The dynamics at play are more intimate to the experience of her characters. And so, maybe, in her explorations of how to build a life in a world that’s transforming beyond recognition, she can teach us how to gird our metaphorical loins.

Reading Order: I’ve constructed my Octavia E Butler reading order mostly as a combination of publication order and story order while prioritizing sequence and saving books I’ve already read for later. It makes a lot of sense!!!, so don’t try to tell me that it doesn’t. Because it does.

My Octavia Butler reading order:

The Patternist Series:

Wild Seed (1980) ✓ (finished 1/20)

Mind of My Mind (1977) ✓ (finished 1/22)

Clay’s Ark (1984) ✓ (finished 1/26)

“A Necessary Being” (in Unexpected Stories) ✓ (finished 1/26)

Survivor (1978) ✓ (finished 1/28)

Patternmaster (1976) ✓ (finished 1/30)

The Lilith’s Brood Trilogy:

Dawn (1987) ✓ (finished 2/6)

Adulthood Rites (1988) ✓ (finished 2/9)

Imago (1989) ✓ (finished 2/11)

Fledgeling (2005) ✓ (finished 2/16)

“Bloodchild” (2005)

Unexpected Stories (2014)

Kindred (1979)

Parable of the Sower (1993)

Parable of the Talents (1998)

Bloodchild and Other Stories (2005)

Btw, in 2016 Sarah predicted the moment we’re living in right now, and after Biden won in 2020 she basically said “I don’t know if this is going to change anything,” and later, after seeing who Biden chose for his cabinet and the action he wasn’t taking, she basically said “Biden is keeping the seat of fascism warm for Trump 2.0 or something worse” and she was correct and was (you guessed it!) maligned for being correct too early.

“The untold story is the black hole around which your story revolves” is another quote that I read once in the early 2000s and has changed my life and I cannot find it anywhere. I once wrote it down with proper accreditation in a journal and that journal was lost.